The story surrounding Arseniy Gonchukov in Israel became one of the most painful and illustrative for the Russian-speaking Israeli community at the beginning of 2026. It was not just a conflict between the author and the audience. It was a break in expectations, intensified by war, questions of identity, and language that proved stronger than the author’s intentions.

To understand why sympathy turned into sharp rejection, we need to start with the basics: who he is, how he ended up in Israel, and why he was perceived not as a guest, but as someone “returning.”

Who is Arseniy Gonchukov and why his arrival was perceived as a return

Arseniy Gonchukov is a Russian independent film director and author who worked outside the official film industry for many years. His films — low-budget, harsh, often marginal — were built around the image of a person “outside the system.” He was not part of the state cultural hierarchy and consciously emphasized his distance from it.

After the start of the full-scale war against Ukraine, Gonchukov left Russia after some time. He arrived in Israel through repatriation — as a Jew exercising his right of return. This is a fundamentally important point: he ended up here not as a tourist, not as a temporary emigrant, and not as an invited guest. He arrived as a person entitled to call Israel his home.

In Israeli society, repatriation is not a formality. It is an inclusion in the collective destiny, even if the person is just beginning the path of integration. That is why he was initially treated not with caution, but warmly.

The first months: how he gained sympathy

In the first months, Gonchukov wrote a lot about Israel. His texts were emotional, sometimes naive, but that was precisely their strength. He wrote about the sea and the air, about cities, people, fruits, the feeling of freedom. He wrote not as a politician and not as an analyst — as a person experiencing a personal discovery.

These texts spread widely on social networks. He later wrote himself:

“I wrote in such a way that everyone believed me… in August, I was shown 9 million post readings.”

In the context of constant international pressure on Israel, such words were perceived as a rare gesture of support. He was invited to meetings, interviewed, and his plans were discussed. He indeed made a film in Israel with the support of a private investor. For many, he became an example of a repatriate who quickly felt the country.

It is important to note: at this stage, he was treated kindly.

He was accepted, not tolerated.

Sudden departure and texts about Moscow

The turning point came unexpectedly. Gonchukov left Israel — and almost immediately began publishing enthusiastic texts about Moscow. About the “homeland,” about the snow, about “the happiness of returning,” about how he missed… Moscow. In one of the posts, he wrote:

“Moscow! Snow! … And the only thing I want to do is go on dates… Now I’m home.”

The departure itself would not have been a tragedy. Israel is a country of migrations. But where he went and how he spoke about it turned out to be decisive.

The value context he did not consider

For a significant part of Israelis, modern Russia is not a neutral space. It is a state:

- conducting an aggressive war against Ukraine,

- killing civilians, including where many Israelis have Ukrainian roots and family memory,

- systematically opposing Israel on international platforms, including the UN,

- openly cooperating with Iran — an existential enemy of Israel,

- supporting and politically covering terrorist structures in the Middle East.

In this context, public joy of returning to Moscow is read not as personal nostalgia, but as a value signal. For many, it looked as if a person who came “home” to Israel just as easily and emotionally confessed love for a country perceived today as hostile.

And here, Israelis really “lost it.”

Reactions of Israelis: from disappointment to harsh accusations

Comments of varying degrees of harshness appeared on social networks:

“Just a regular Russian, what did you expect? Don’t let them in.”

“He sold himself for love for Israel. And then returned to Moscow — everything became clear.”

“I’m not hurt that he returned. I’m hurt that we made an idol again and were disappointed again.”

The last type of reaction was the most mature, but it drowned in the general noise. The common motive was one: the feeling of betrayed trust.

Climax: hitting the most sensitive spot

The conflict could still be mitigated. Many expected Gonchukov to be cautious, to distance himself from Russian politics, to empathize with the pain of people for whom Russia is a source of threat and loss.

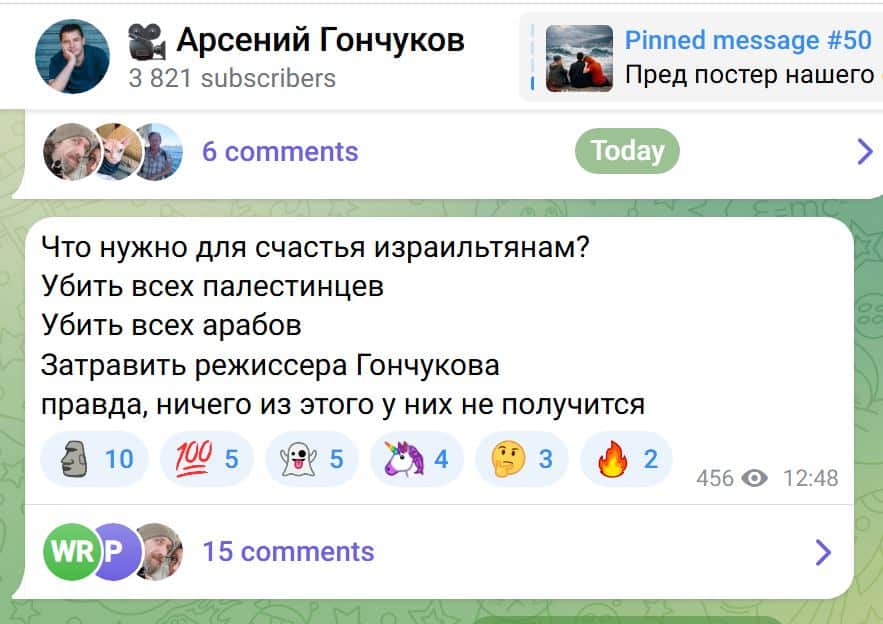

Instead, he chose escalation. The climax was a phrase in his Telegram account on January 12, 2026:

“What do Israelis need for happiness?

Kill all Palestinians

Kill all Arabs

Harass director Gonchukov”

In the Israeli context, this did not sound like irony. It was perceived as attributing genocidal intentions to an entire people — precisely the language with which Israel has been attacked by its opponents for years.

After this, trust collapsed completely.

Why it was considered Z-rhetoric

It is important to emphasize: it’s not about Gonchukov consciously working for propaganda. It’s about his formulas coinciding with the language of the Z-narrative.

Modern propaganda works not with slogans, but with meanings:

- collective guilt,

- erasing differences between radicals and society,

- accusations of mass murder,

- cynical sarcasm instead of analysis.

All these elements were found in one paragraph. In the conditions of war, this was enough.

How his words fit into the anti-Semitic and anti-Zionist narratives of Israel’s enemies

Not only the emotional reaction of Israelis deserves attention, but also the content side of what Arseniy Gonchukov actually said — and in what informational field these words already exist.

The key problem here is not the author’s personal offense and not his artistic manner. The problem is that some of his formulations exactly matched the basic anti-Zionist and anti-Semitic theses that have been used for decades by Israel’s enemies — from Iranian propaganda to Russian official and semi-official channels.

1. Attributing genocidal intent to Israelis

The phrase:

“What do Israelis need for happiness?

Kill all Palestinians

Kill all Arabs”

— is not just harshness and not just hyperbole.

It is a classic formula of anti-Zionist accusation, according to which:

- Israel as a state,

- and Israelis as a society

allegedly collectively strive to destroy Arabs.

This logic is at the core of:

- accusations of Israel of “genocide” on international platforms;

- resolutions and statements promoted by countries hostile to Israel;

- street agitation of radical movements in Europe and the Middle East.

When such a formula is voiced by a Jewish repatriate, it is perceived especially painfully. Not because “a Jew cannot criticize Israel,” but because he reproduces an accusation used against the very existence of the Jewish state.

2. Erasing differences between radicals and society

In Israeli public discourse, there is a fundamental difference between:

- criticism of specific politicians,

- criticism of the government,

- discussion of radical statements by individual groups

and generalization to the entire people.

Gonchukov did not make this distinction.

The formula “Israelis need” automatically:

- makes all Israelis subjects of violence;

- erases differences between extreme marginals and the majority of society;

- turns the complex reality of war into a caricatured image.

This is another key technique of anti-Zionist propaganda: to present Israel as a monolithic society obsessed with destroying “others.”

3. Coincidence with Russian foreign policy rhetoric

It is important to consider the geopolitical context in which these words were spoken.

Russia:

- regularly votes against Israel or abstains in key UN resolutions;

- publicly accuses Israel of “excessive violence” and “collective responsibility”;

- supports and develops strategic partnership with Iran;

- politically and informationally covers terrorist structures in the region.

Against this background, the words of a person who returned to Moscow and publicly confessed his love for it are automatically read as reinforcement of this line, even if the author himself does not realize it.

This is the key point:

the anti-Zionist narrative works not with intentions, but with effect.

4. Self-centered shift of focus

The third point of his phrase —

“Harass director Gonchukov”

— finally shifted the focus from the reality of war and people’s pain to the figure of the author himself.

In the eyes of Israelis, it looked like this:

- first — accusation of society in genocide,

- then — shifting the conversation to the plane of personal harassment.

Such a construction is characteristic of another anti-Semitic motif — inversion of the victim, where real violence and real threats are devalued, and the central sufferer is declared to be an external observer.

5. Why the argument “I didn’t mean it” didn’t work

The Israeli reaction was harsh not because someone “didn’t understand the irony.” But because in the conditions of war, society reads not the subtext, but the structure of the statement.

And the structure was as follows:

- collective accusation;

- coincidence with the rhetoric of enemies;

- lack of distance;

- lack of empathy;

- escalation of conflict instead of its resolution.

That is why attempts to explain what was said as an artistic device or emotional breakdown did not change the perception.

Arseniy Gonchukov might not have been an anti-Semite and might not have considered himself an anti-Zionist.

But his words objectively fit into the anti-Semitic and anti-Zionist narratives with which Israel is attacked by its enemies — politically, informationally, and morally.

In the conditions of war, this was enough for:

- sympathy to turn into rejection,

- a personal story to become a public conflict,

- and the figure of the author to become a symbol of dangerous blindness to context.

Psychological analysis: what this phenomenon is (popular science)

From a psychological point of view, three mechanisms converged here.

1. The effect of “moral privatization”

A community under threat tends to appropriate those who speak well of it. A compliment is perceived as a sign of loyalty. When a person leaves, it is experienced as betrayal — even if there was no formal obligation.

2. Cognitive dissonance

People cannot hold two contradictory ideas in their minds:

“he loves Israel” and “he sincerely loves a country hostile to Israel.” To relieve tension, the mind chooses a simple explanation: he must have been lying.

3. Projection and aggression in wartime conditions

War enhances the need for clear boundaries of “us vs. them.” Any uncertainty causes anxiety. Aggression directed at a “borderline figure” is a way to relieve this anxiety.

Gonchukov turned out to be just such a figure.

Conclusion: why sympathy turned into a break

The transition was not sudden, but sequential:

- Repatriation and warm reception.

- Public love for Israel.

- Sudden departure and delight at returning to an aggressor country.

- Refusal to consider the Israeli and Ukrainian context.

- Hit on the most sensitive spot — accusation of genocidal intentions.

Gonchukov had the right to personal choice. But public speech in wartime conditions ceases to be only personal. It becomes a political fact — regardless of the author’s intentions.

This story is not about censorship and not about banning feelings. It is about how detachment from context and the use of language coinciding with enemy propaganda turn yesterday’s sympathy into a harsh break.

And this is a lesson that Israel still has to comprehend.