In the section “Jews from Ukraine” read the story of Solomon Frankfurt — a Jewish scientist and organizer of science, who in the early 20th century helped Ukraine build what today would be called “agro-innovation infrastructure”: laboratories, experimental fields, breeding stations, seed quality standards, and applied research tied to the real economy.

This biography (Ukr.) was compiled by Israeli author Shimon Briman on the website Ukrainian Jewish Encounter. He writes about Frankfurt without romanticizing — as a person who spoke equally confidently in the language of chemistry, agricultural practice, and state decisions. And that is why in Ukrainian agricultural history, Frankfurt has a figurative nickname: the network of scientific centers around Kyiv was later called the “Temple of Solomon” — not in a religious sense, but as a metaphor for a “built system” that survived the change of eras.

Who is Solomon Frankfurt — briefly, but to the point

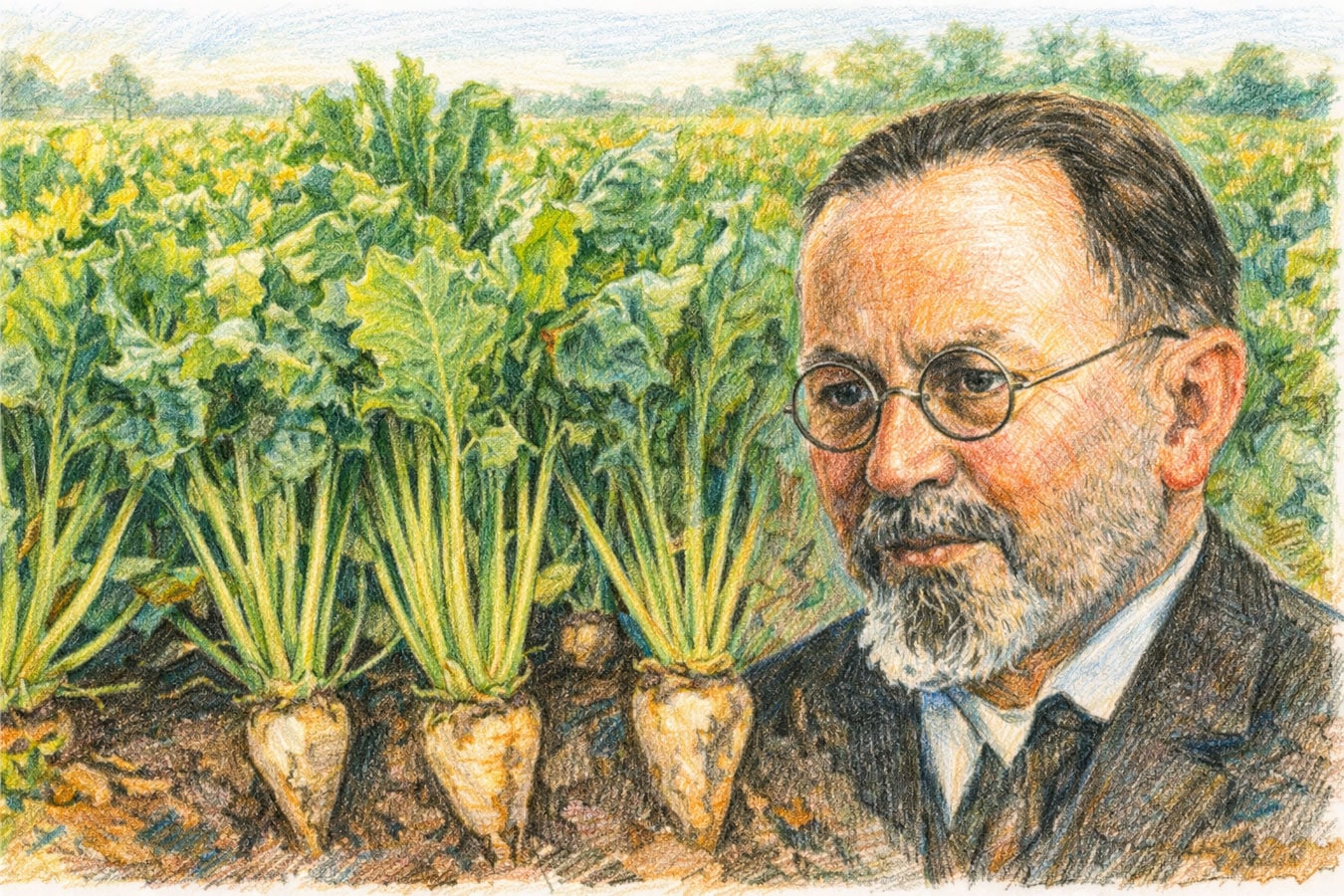

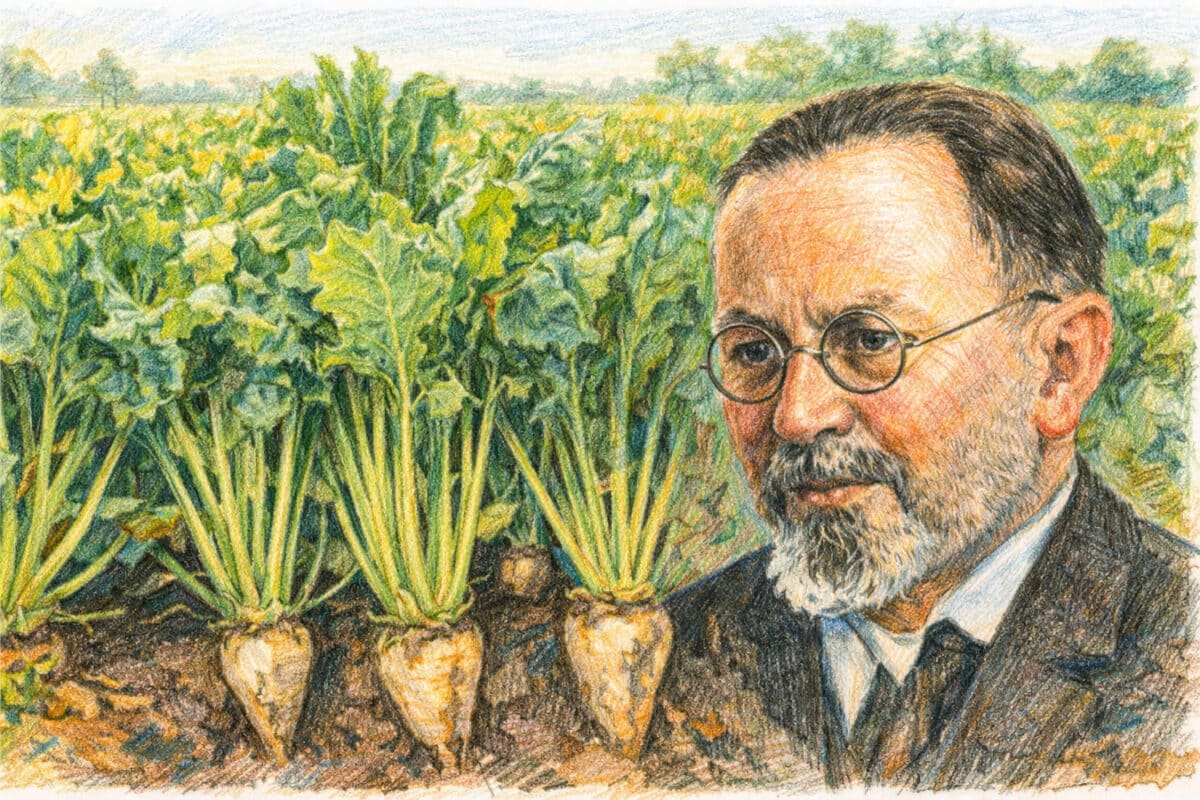

Solomon Lvovich (Shlomo Meirovich) Frankfurt was born in 1866 in Vilno (now Vilnius). He received a European education and a doctorate in chemistry in Zurich, researching sugars in plants — a topic that directly intersects with Ukrainian beet growing and the sugar industry of the early 20th century.

But an “imperial career” for a Jewish scientist at the end of the 19th century often did not depend on abilities. Briman cites a telling episode: in 1898, Frankfurt was denied a professorship at the Moscow Agricultural Institute precisely because of his religion. In simple terms, it sounds like this: the road to universities is closed — so science must find a way through practice.

And Frankfurt found this way in Kyiv.

Kyiv: the laboratory from which the system grew

Moving to Kyiv was a turning point for Frankfurt. In 1901–1920 (Briman highlights this period as the most productive), he worked where science meets real production: sugar factories, agrochemistry, seed quality, yield.

Frankfurt headed the agrochemical laboratory of the Kyiv Agricultural Syndicate and began promoting what today seems obvious but was then new managerial thinking: seeds should not just be bought and sown, but checked, compared, improved, standardized. Science should measure results, not serve beautiful reports.

Briman emphasizes that from this laboratory over time grew a functioning scientific center at the specialized Institute of Agriculture. That is, it is not about a “flash of talent,” but about creating an institutional base: structure, people, methods, a habit of experimentation.

Experimental fields and fertilizers: work not in theory

Frankfurt did not confine himself to office chemistry. According to Briman, he participated in creating a network of experimental fields in several provinces — to test ideas not on paper, but in soil and weather. This is important: Ukraine is vast and diverse, and universal recipes in agriculture work poorly.

A separate direction was work with mineral fertilizers. At that time, it sounded like a “modernization tool” — an opportunity to increase yield and stabilize product quality. In the text, Frankfurt appears as a person who explained to producers and landowners: yes, it’s money, yes, it’s technology, but without it, the agro-economy will lag behind.

Briman essentially shows a “transition model”: from agriculture as a tradition — to agriculture as an industry where decisions are confirmed by data.

Myronivka and “Ukrainka”: when selection becomes part of the country

One of the key episodes is the organization in 1909 of the Central Research Station for Sugar Beet Culture near Myronivka. Briman writes that the station was supported by local sugar manufacturers: this is an important link between science and business, without which infrastructure usually does not survive.

Later, based on these initiatives, the Myronivka Breeding Station (today — the Institute of Wheat) appeared. And here Briman gives a detail that catches even people far from the agricultural topic: Frankfurt is credited with the authorship of the idea of naming the winter soft wheat variety “Ukrainka 0246.”

This is not a trifle. The name of the variety is a symbol that “Ukrainian” can be not only a political declaration but also a specific product of science: grown, tested, distributed.

Frankfurt and Ukrainian statehood: a choice that was not “neutral”

Briman shows Frankfurt as a person who did not hide from politics — although he was not a political tribune. During the Ukrainian revolution, Frankfurt participated in creating professional and scientific structures, worked in commissions, and dealt with what often remains behind the scenes: the institutional design of the industry.

The text contains a thought that Briman formulates harshly and without embellishments:

“He believed in Ukrainian statehood more than many Ukrainians” — writes Briman.

Separately noted is the work under the Hetman government, where Frankfurt dealt with agriculture and food issues and participated in preparing agricultural legislation. That is, it was not “sympathy in words,” but involvement in managerial routine: documents, norms, rules.

Negotiations of 1918: economic diplomacy and sugar

There is also an international layer. Briman cites the position of historian Ruslan Piroh: Frankfurt twice represented Ukraine in complex economic negotiations with Germany and Austria-Hungary in 1918. The essence — the Ukrainian side defended economic conditions, including a fair price for Ukrainian sugar.

Briman emphasizes: it was not a “symbolic trip,” but negotiation work where each figure had political weight.

The text also mentions Frankfurt being awarded a German order — as a marker of recognition of his role in these contacts.

Emigration and World ORT: continuation of the Ukrainian biography in the world

After the defeat of the UNR, Frankfurt, according to Briman, refused to cooperate with the Bolsheviks and emigrated at the end of 1920. Then another part of life begins — but it logically continues the first: building a system, only now at an international level.

For decades, Frankfurt worked at World ORT — an organization engaged in technological education and support for artisans and farmers. Briman lists the cities and stages of ORT’s European work, and then the move to the USA. From 1947, Frankfurt became the president of World ORT.

He died in 1954 and was buried in New York State. But the Ukrainian trace in his biography did not disappear: Briman builds the line so that the reader sees — the experience of creating agricultural infrastructure in Ukraine became part of his broader, global project.

Why “Temple of Solomon” sounds especially poignant today

The metaphor “Temple of Solomon” Briman associates with the assessment of academician Viktor Vergunov: it is about the agricultural scientific centers of Ukraine created by Frankfurt, which worked even after him. The meaning of the metaphor is in the built “architecture of science”: when the system continues to function, even if the creator is long gone.

The finale with Briman is modern and very direct: he reminds that Jewish school No. 141 in Kyiv, operating under the aegis of ORT, is experiencing a difficult military winter — with shelling, power, and heat outages. The story of a person from the early 20th century suddenly turns out to be close to the reality of 2026.

Main conclusions for the section “Jews from Ukraine”

Frankfurt is an example of a Jewish intellectual who became part of the Ukrainian modernization project not with slogans, but with infrastructure.

His contribution is not one “loud idea,” but a habit of scientific verification, standardization, and systematic experimentation in agriculture.

During the Ukrainian revolution, he made a conscious choice in favor of Ukrainian statehood and worked in real managerial mechanisms.

His subsequent work at World ORT shows the continuation of the same logic: education, applied skills, community support — through institutions, not declarations.

Text: Shimon Briman (Israel). https://ukrainianjewishencounter.org/uk/hram-solomona-bilya-ki%d1%94va-yak-%d1%94vrejskij-vchenij-prosuvav-agroindustriyu-ukra%d1%97ni/

The author is grateful to the employee of the World ORT Archive in London, Jennifer Brunton, for assistance in finding materials and providing a photograph of Solomon Frankfurt.